Schools should be representative of the world we want to live in: diverse, thriving, and with equal access to opportunity.

New research by Industry Professor Michele Bruniges AM reveals that concentrations of disadvantage in Australian schools are intensifying, undermining the country's commitment to providing equal educational opportunities for all.

Australia has a strong and proud tradition of a fair go for all. The promise of our egalitarian society is that anyone can succeed regardless of where they are born or who their parents are.

The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration was signed by all Education Ministers in 2019. It is an agreed statement that echoes the values and beliefs of the broad education community and sets the direction for all States and Territories. The Declaration has an unambiguous focus on excellence and equity. It speaks to an explicit focus on educational disadvantage and amplifies this in the following commitment to action.

Yet the reality is that our education system does not yet deliver the same educational opportunities and support for every child.

Sadly, today, more children are experiencing socio-educational disadvantage than ever before, driven by a range of factors, including postcode, family circumstances and disability.

Supported by UTS and the Paul Ramsay Foundation, Industry Professor Michele Bruniges AM’s research shows the concentration of disadvantage across the school sector has intensified in just a short space of time.

Addressing this is crucial for fostering a more equitable education system that allows all students to thrive academically and socially.

Michele Bruniges AM is an Industry Professor – Concentrations of Disadvantage at the UTS Centre for Social Justice & Inclusion and a Paul Ramsay Foundation Fellow. She is an experienced educator and leader in the field of education policy.

Concentrations of disadvantage are increasing in all sectors

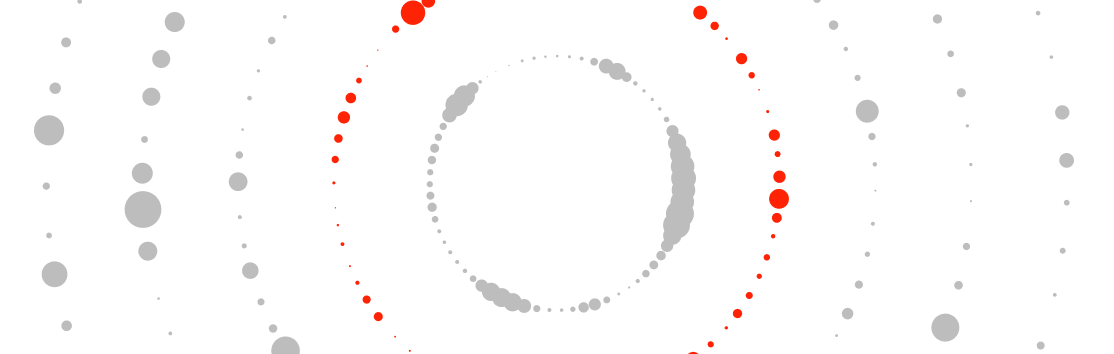

Since 2017, there has been an increasing trend in students from disadvantaged backgrounds being clustered in the same schools.

While all sectors, Catholic, Independent and government, show increasing numbers of schools in this situation, public schools carry a disproportionate load.

In 2017, 17 per cent of Australian schools were classified as having a high concentration of disadvantage (defined by at least 50 per cent of students falling into the lowest quartile of the socio-educational advantage scale).

By 2023, this rose to 20 per cent, taking the number of high-concentration schools to more than 1500 – directly impacting 555,000 children and teenagers. Government schools, not surprisingly, were over-represented.

This clustering of children who often need additional support puts extraordinary pressure on school resources and teachers, impacting educational and life outcomes.

This lack of socioeconomic diversity also creates a cycle of negative consequences for communities. We see schools that are working the hardest labelled negatively and shunned by local families with the means to send their children to other schools. This leads to widespread disconnection from the community and cements pockets of disadvantage.

But we can turn this around.

When children – regardless of where they live – have access to high-quality learning environments, they do better in school and are set to thrive in later life, helping drive better outcomes for families, the economy and the whole community.

Targeted interventions and policies to mitigate concentrations of disadvantage

There is not one answer, but there are a range of things we can do at the local, state, territory, and national levels that could make a difference.

Working with colleagues from all states and territories and sectors, several case studies have identified actions that schools and communities are taking at the local level to make a difference, including:

- Addressing basic needs, such as ensuring all children have access to healthy meals at school.

- Strengthening family engagement in schools to support student learning.

- Providing evidence-based resources to support teaching and learning.

The research has also proposed several policy reforms that should be considered as part of the solution, including:

- Adjusting school zoning to challenge the way postcode concentrates both wealth and disadvantage.

- Asking more of schools that receive government funds to open their doors to children from less advantaged backgrounds.

- Considering whether newly registered schools be required to be comprehensive – not specialist or selective – with consideration given to the impact on surrounding school socio-educational advantage profiles and enrolments.

- A clear set of mutual obligations on schools for the receipt of taxpayers’ dollars demonstrating clear public benefit and national interest.

This will be a challenging conversation because it lays bare the disparities. But until we find ways to connect different school communities and break down these barriers to opportunity, we will condemn our children and young people to far less.

Case studies: Educational excellence in a challenging environment

Equity must be at the heart of the education sector. It’s essential for Australia’s future that everyone has the opportunity to use their skills and capabilities to tackle our biggest challenges. Dr Bruniges’ research will offer new thinking and policy recommendations that ensure every child has a fair chance to achieve success.

Amy Persson

Interim Pro Vice-Chancellor (Social Justice and Inclusion)

UTS is grateful for the significant investment from the Paul Ramsay Foundation in support of this research and for the opportunity to be a part of the cohort of Paul Ramsay Foundation-funded organisations.