An economically viable climate change solution

Plant-based plastics. Photo credit: Maya Cook.

In January, Southern California’s overgrown and dry undergrowth went ablaze, taking 29 lives and destroying thousands of homes. “The atmosphere has warmed up so much,” UTS Professor Peter Ralph explains, “that it has become a huge sponge that sucks up moisture quickly and dries out the vegetation and land – or it can empty the sponge causing massive rainfall events.” In February, Northern Queensland experienced such rainfall that it resulted in devastating one-in-a-hundred-year flooding. Due to climate change, weather extremes like these are becoming an increasingly common occurrence across the globe.

Distinguished Professor Peter Ralph holding a bioplastic mini brick developed by C3. Photo credit: Maya Cook.

In its commitment to matching industry sector knowledge, insights and needs with internal research expertise, UTS’s work in Climate Remediation and Decarbonisation is part of the University’s deep sector engagement strategy, which also includes Agriculture/Horticulture Technologies, Health, Space and Defence.

Distinguished Professor Peter Ralph is the Executive Director of the Climate Change Cluster (C3) research institute in the UTS Faculty of Science, one of our key institutes working to provide climate mitigation solutions. “A challenge is that society is watching as the climate crisis evolves, and the lack of immediate action is perpetuating the problem.” Professor Ralph continues, “We need to be able to influence society, not to panic society, but to show economically viable ways to address climate change and still keep society ticking.”

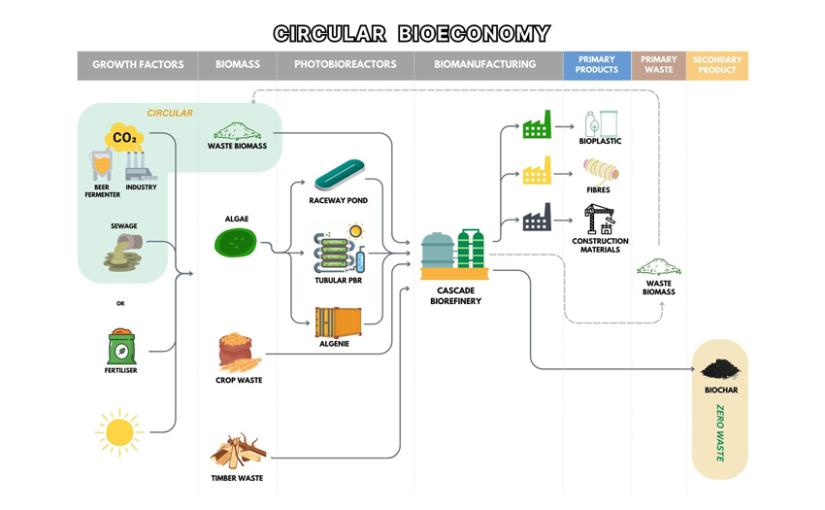

C3 sees the bioeconomy – defined as the production of energy, goods, and services using biomass (biological material, like wood, seaweed, etc) and biotechnology – as the most promising avenue to influence society towards climate solutions. Key to the C3’s bioeconomy strategy is to encourage industry away from fossil-based production and towards plant-based production.

Bio-manufacturing alternatives

“The energy that we use for cheap manufacturing, and the raw materials that go into making most of our plastic products, is fossil-based, causing the atmosphere to warm.” Ralph holds up a pen, “But did you know we could make the plastic in this pen using seaweed?” He presents several small building blocks of plant-based plastic that have the same density and rigidity we have come to depend on from our plastic products. These plastics, made from seaweed biomass, have retained their high carbon content within their structure, making them a carbon sink rather than a carbon source.

High-rate algae pond. Photo credit: Rocky de Nys.

In addition to their sustainability, bio-manufactured goods have the potential to be functionally superior to their fossil-based counterparts. Professor Ralph points to a cube of plasterboard, a building material traditionally made from carbon-emitting gypsum. Ralph’s sample cube of plasterboard contains saltwater algae, and it has a plaster setting-time that can be customised, faster or slower, based upon the types of algae used in its production.

Professor Ralph then shows off a swatch of cloth, with the same look and texture as cotton. This cloth, however, was created from a freshwater macroalgae that could be grown using agricultural waste as a natural fertiliser, which cleans the water of the waste nutrients in the process. “When we overfertilize cotton crops throughout Western NSW, excess fertiliser runs into the river. The river becomes a microbial soup, removing the oxygen and killing the fish. But when we produce this bio-manufactured cotton alternative, made from macroalgae, it will take nitrogen and phosphorus out of wastewater and mitigates against these potential environmental problems.”

An opportunity for Australia

In its bio-manufacturing advocacy, C3 is incorporating expertise from across the university. It’s a pan-university approach that also reaches beyond university faculties into partnerships in government, industry, and the extended alumni and university communities.

“Australia is in the perfect position to pivot to a much more sustainable bioeconomy,” Ralph explains. “We've access to renewable energies to make products cheaper than the rest of the globe. You can’t make these products in northern Germany because northern Germany doesn't have the same amount of sunlight and access to seawater required to grow the biomass.”

The intersection between circular economy, biorefinery, and biomanufacturing. Photo credit: Maya Cook.

Transitioning domestic manufacturing industries to bio-based production doesn’t have to require a start-from-scratch rebuilding of current infrastructures. Many of Australia’s underutilised or abandoned manufacturing systems can be converted, changing from black fossil feedstock to green renewable feedstock. It’s an industry ripe for disruption and keen entrepreneurial minds.

“That's the opportunity in the market, to recognise a cheap underutilised manufacturing facility and then get a producer to have renewable feedstock available for the manufacturing supply chain. In Australia, over the last 50 years, we've abandoned our manufacturing system so there’s little home-grown manufacturing, but today we have the means to use our abundant sunlight and saltwater to change that, to turn Australia into a leader in bio-manufacturing. We can produce products from biomass that help make the planet cooler instead of hotter, and we will be the showcase for the world. In C3, we are tackling these challenges head-on by innovating these products from renewable resources like algal biomass. Our commitment extends beyond development; we are actively collaborating with industry partners to scale these solutions. Our mission is clear: to deliver these groundbreaking solutions directly to those who need them most.”

Learn more about C3, how to partner with C3, and how UTS partnerships are addressing the climate crisis. To contact the institute directly, please email climatechangecluster@uts.edu.au